Home » A Tale of Two Americas: The Cantillon Divide in Modern Finance

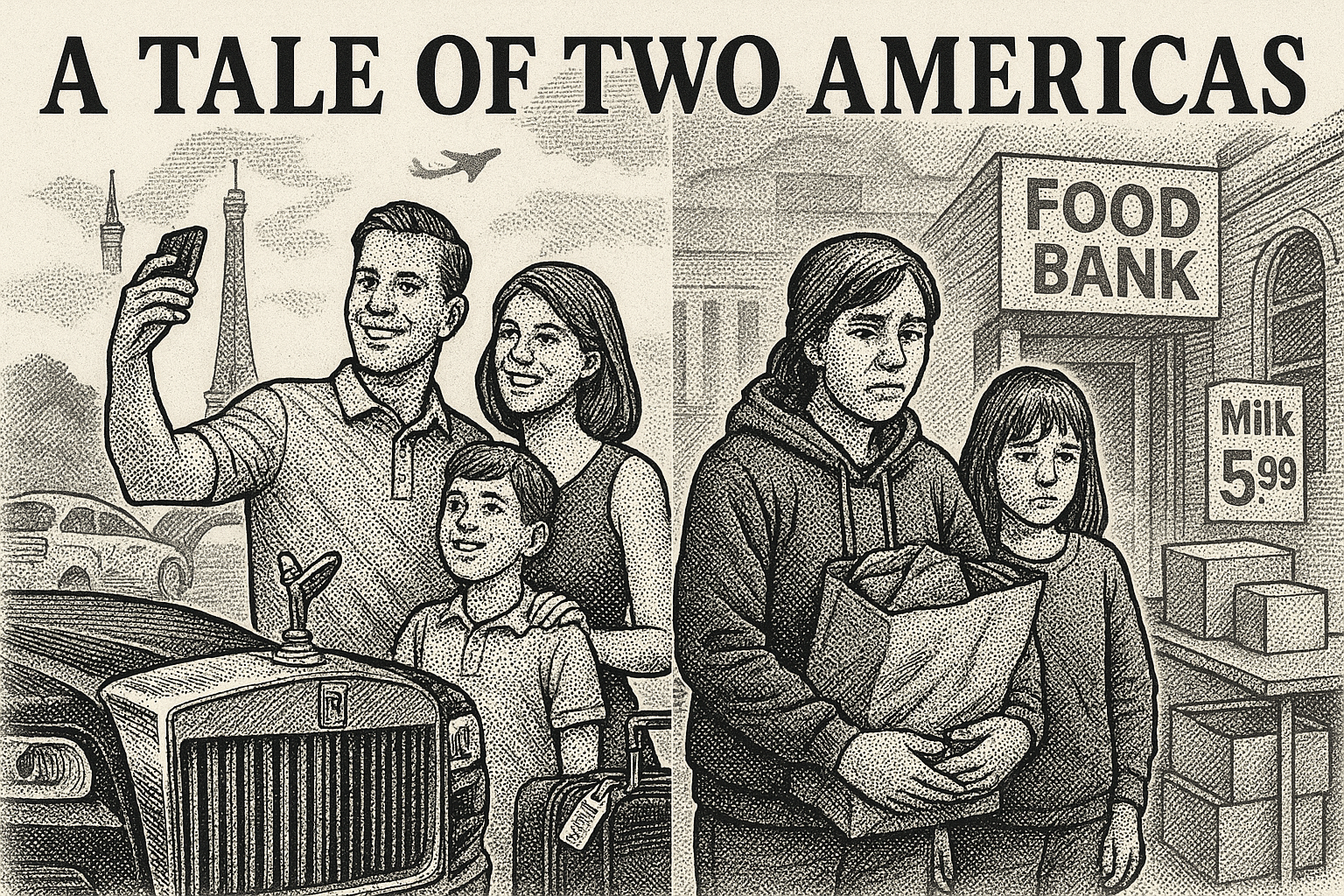

A Tale of Two Americas: The Cantillon Divide in Modern Finance

Related topics:

FREE WEBINARS

for dedicated Financial Advisors

All Times in US-Pacific

About Mark McKenna Little

Mark Little is the ‘regular guy’ Financial Advisor whose unconventional approach to financial services acquired 1,242 clients.

Then in just 34 months he rebuilt his business from the ground up, shattering international records and boosting revenue by 412%

Free Membership includes

- The Only Game In Town: (audio) 10 Game-changing Strategies for Financial Advisors

- Acquiring Successful, Affluent Clients: 10 Critical Lessons for Gaining Affluent Clients

- Become the ‘Most-Trusted’ Financial Advisor: 10 Essential Lessons for Successfully Serving Affluent Clients

- The Kate Wilson Case Study: (audio) Learn how a Real Life Financial Advisor Rapidly Transformed her Practise using Mark’s advice.

- Mark’s Weekly Digest: valuable insights and updates, delivered to your inbox.

(Opt Out any time via any issue)

No credit cards, Unsubscribe any time, No strings attached (just sign up for instant access)

Responses